Last October I was given the chance to attend the “iRALL school on field data collection, monitoring, and modeling of large landslides” in Chengdu, China. During the school, we spent one week in the epicentral area of the Ms=8.0 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, where I was able to take some interesting pictures of earthquake damage and coseismic landslides. Then other things happened, like the earthquakes in Italy and New Zealand, with exciting sights from the field shared here, and I never ended up sharing my Wenchuan pics, which I want to do now.

I have reported about iRALL, the international Research Association for Large Landslides, before, and also about my visit at the epicentral area of the Wenchuan earthquake and a post-earthquake debris flow in 2015. The 2016 iRALL school started with a week of lectures and laboratory training given by international landslide experts at the State Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention and Geoenvironment Protection (SKLGP) in Chengdu. In the second week we travelled to Beichuan, a town close to the epicenter of the earthquake, for a field training on coseismic landslides guided by international experts, such as Mauri McSaveny from New Zealand, Hans-Balder Havenith from Belgium, and Cees van Westen from the Netherlands.

Beichuan town

Many might remember that the 2008 earthquake caused over 80,000 fatalities. Of those, more than 20,000 were killed in the Beichuan county town, as the Longmenshan fault zone runs right through it. The ruins of Beichuan are now a memorial park. Meanwhile, the town was reconstructed in a safer place on the footwall of the fault (yes, the hotel was on the footwall as well). Old Beichuan is located at this narrow bend of the river (see map on the image below), while the fault runs roughly from SW to NE, with the footwall on the southeastern side. Everything that was located on the hanging wall here got basically crushed during the earthquake. I will try to let the photos speak for themselves now.

View from south of the river bend (map) towards the hanging wall. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

A damaged hotel. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

Earthquake damage. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

It is interesting how these houses are all tilted in different directions. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

Typical X-shaped cracks. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

We were permitted to enter this tilted house located on a slope on the footwall of the fault, which left us with weird feelings, something between “being drunk” and “the house is still moving”. Apparently it is still being used for storing tools and crops.

Tilted house on the slope, footwall. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

Here the group is standing on an 11(!) meter fault scarp. The house is luckily located on the footwall. However, it used to have a valley view.

Group photo on an 11 m fault scarp.

Part of the memorial park is also a museum that was built in the new town and opened in May 2013. The stunning architecture is likely to make geologist’s hearts beat faster. Seen from above it looks like a fault zone itself. The exhibition is also pretty impressive, making the visitors go through the moment of the earthquake, the paralyzing feeling right after the shock, and the painful struggle in the days, weeks, months, and years after the earthquake. It is amazing and remarkable how the Chinese people managed to find the strength to go through this nightmare.

The Wenchuan Earthquake Memorial Museum. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

The landslides

During the week in the field we also visited three large landslides that were triggered during the earthquake. All three landslides also produced landslide dams. Some of these dams had to be artificially bypassed in the aftermath of the earthquake, in order to prevent sudden outburst floods.

Landslide No. 1: Tangjiawan landslide

Tangjiawan landslide was triggered during the Wenchuan earthquake, and it was reactivated in September 2016. The outer scarp on the map below is the original coseismic scarp, while the middle scarp is the one of the reactivated landslide. Together with Cees van Westen and Xuanmei Fan we mapped the landslide with the help of an aerial photograph.

Map of Tangjiawan landslide.

In the field the landslide looked much steeper than on the map.

The landslide formed a dam, that is now neatly piled up and bypassed by the river. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

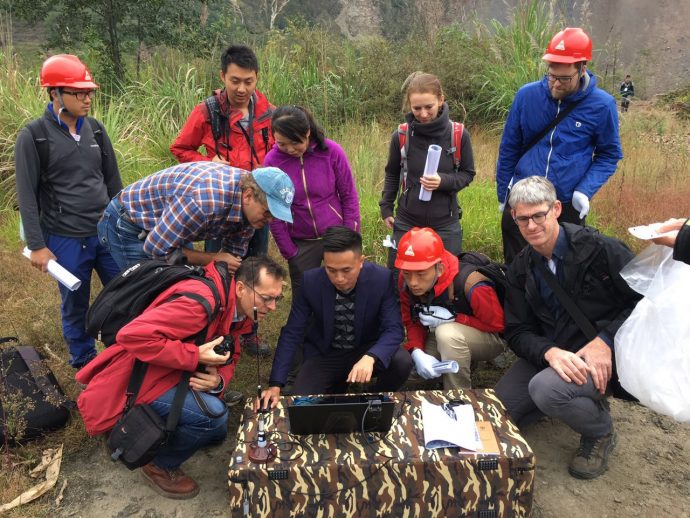

We were also able to take part in a demonstration of a really advanced, no-worries-all-included-hours-of-battery-lifetime-UAV-SfM system. Pretty impressive, if you can afford it…

Takeoff. Photo by Lukáš Janků.

Checking the flight path of the UAV directly on the computer with a mixture of amazement and skepticism.

Later, Mauri McSaveny took us on an expedition to the sliding surface, where we found some completely crushed rock material and plastic clays.

“Inside” of the landslide.

Landslide No. 2: Landslide near Qinglin

The second landslide was barely visible in the field. Here, we did some geophysical measurements under the supervision of Hans-Balder Havenith for finding the sliding surface. With a CityShark II we measured the ambient noise on different positions on the slope, and later, by analyzing the H/V (horizontal to vertical) ratio of the ambient noise we could locate the depth of the sliding surface.

Ambient noise measurements with the CityShark II.

Landslide No. 3: The mind-blowing one

Luigi, one of the participants who visited this landslide earlier, warned us to be ready to have our minds blown before we departed for this one. And for once he had absolutely not exaggerated. It was already hard to capture the huge landslide in one picture. This is only an attempt.

Scarp area and landslide dam.

And then we saw sulfide oxidation in action. Sulfide oxidation is a chemical reaction that occurs when sulfide minerals, such as pyrite, are exhumed after a long time of burial and get into contact with oxygen. Usually this phenomenon is known from mining.

This dude is slowly working his way through the landslide dam, while being a good scale for making aware of the dimensions.

Landslide dams can actually form pretty scenic lakes.

I want to thank iRALL and the SKLGP for this opportunity. As usual, everything was perfectly organized. There will be a 2017 edition of the iRALL school, so if you are a PhD student or Postdoc interested in large landslides you should go ahead and apply. Moreover, many thanks go out to Lukáš Janků from New Zealand for sharing his pictures, to the teachers for sharing their know-how, and to the fellow students for the fun time we had together.

Maurice L. | 2017-03-25|02:57 (UTC)

Thank you Anika. Impressive pictures. Were all landslides in rock formations?

munawar | 2019-04-10|05:04 (UTC)

It was an informative and impressive gathering, where i learnt too much.

missing all