A recent study presented at the GSA meeting concludes that the UNESCO World Heritage site of Machu Picchu in Peru was intentionally built on faulted bedrock in order to ease the quarrying of the huge blocks used as construction material (Menegat, 2019). But has Machu Picchu seen big earthquakes in its lifetime? And if so, can it tell us something about their magnitude? After all, there are plenty of earthquakes in Peru, not only at the subduction zone but also in the Andes (e.g., Wimpenny et al., 2018). Some strong instrumental events occurred less than 100 km away from the Inca site. However, in the area of Machu Picchu we knew little about strong earthquakes. That’s why in 2016 a group of researchers from Peru, France, and the UK including myself started to investigate the active faults around Cusco and archaeoseismological damage to Machu Picchu and other famous Inca sites nearby in the CUSCO-PATA project.

Archaeoseismology

The rationale behind “archaeoseismology” is pretty straight forward. From modern earthquakes we know the patterns of damage to infrastructure and all kinds of old and new buildings. We also have a good idea on the relation between the degree of damage and its relation to magnitude/intensity and other earthquake parameters. We can use these modern observations and apply them to archaeological sites in order to detect earthquake damage that is much older. As in Machu Picchu, we can then extend the earthquake record beyond the limits of written sources.

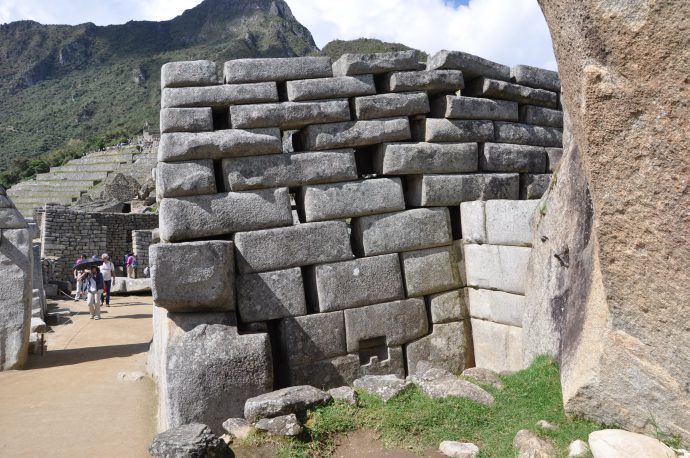

Of course it’s not that easy. One has to make sure that the damage is really due to earthquake impact and was not, for example, caused by soil creep, landslides, warfare, etc. Typical earthquake damage patterns observed in archaeological sites include corner break-outs, rotated blocks, tilted and folded walls, folded pavement, and damaged arches (Rodríguez-Pascua et al., 2011).

Damage in Machu Picchu

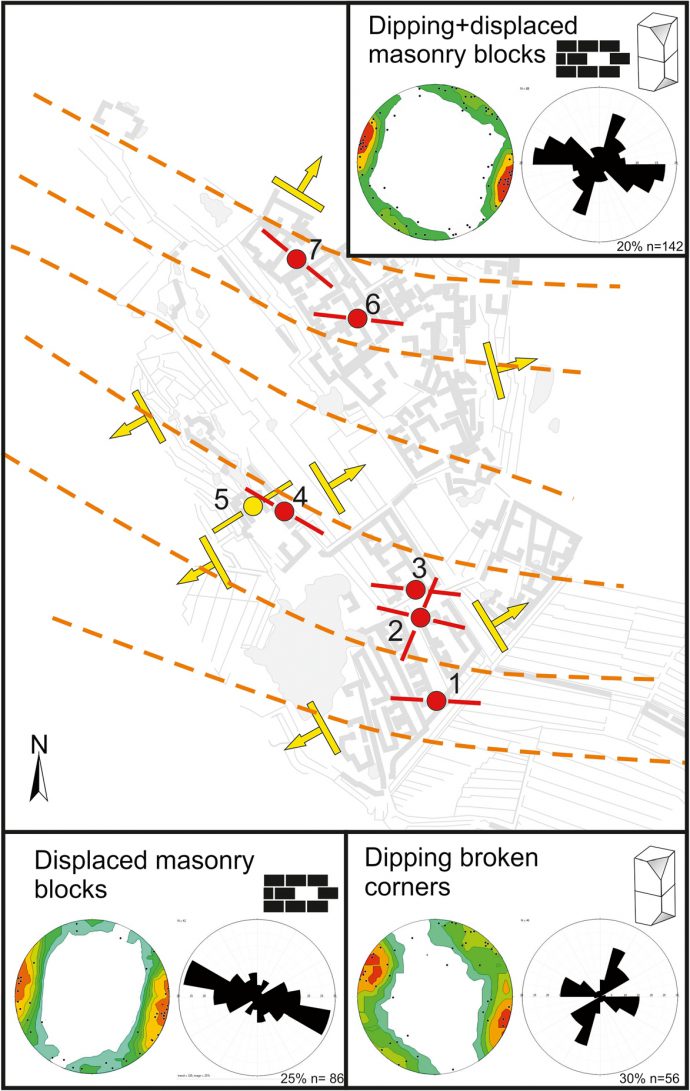

In our study we focussed on the Temple of the Sun (Templo del Sol), the Main Temple (Templo Principal), and the Three Windows Temple (Templo de las Tres Ventanas). We identified 142 deformation features and measured their amplitude (e.g., offset of blocks) and main orientation. Interestingly, there are two clear populations of damage that are oriented 025° and 110°, respectively. Those sites sitting on a slope known to be creeping, like the Main Temple, have a third preferred damage orientation of 60°-80°, that is, perpendicular to the slope as expected. This means that soil creep clearly dominates the deformation pattern of some buildings, but can’t account for the damage observed elsewhere. Thus, we infer ground shaking as the probable cause. The two predominant directions may indicate one or two earthquakes, but this is hard to tell.

ground motion.

Age of the earthquake

In Machu Picchu one can observe two different building styles. The lower parts of many buildings and walls are made up of impressive masonry made of large polygonal blocks that perfectly fit. The upper parts are constructed in a simpler style with smaller stones. This change in building style is interpreted by archaeologists to reflect a crisis during construction, after which the Incas changed to a cheaper and less sophisticated way of building the city. All the damages that we mapped are restricted to the lower sections of the wall with the impressive polygonal walls. This means that the earthquake happened during the construction of the city between 1438 and 1491, or caused a major phase of repair. Machu Picchu was abandoned in the mid-16th Century, which therefore post-dates the earthquake.

Conclusions

Machu Picchu is not only an amazingly beautiful site, but also interesting from a geological point of view. Our study is the first to find evidence for an earthquake during the construction period, which is pretty important because the record of strong earthquakes in Peru is rather short. Paleoseismological studies may reveal the causative fault in the future. So far we have focussed our trenching on the Cusco area (read more on this here), but for sure there is a lot to learn from the wider Machu Picchu area. However, the conditions for trenching will be challenging: extremely steep slopes and poor accessibility. Our study also has some important lessons for the seismic hazard of this area in general, and for the protection of the UNESCO World Heritage site from geological hazards in particular.

The study was recently published in the Journal of Seismology.

References

- Menegat, R. (2019, September). How Incas used geological faults to build their settlements. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs (Vol. 51, No. 5).

- Rodríguez-Pascua, M. A., Pérez-López, R., Giner-Robles, J. L., Silva, P. G., Garduño-Monroy, V. H., & Reicherter, K. (2011). A comprehensive classification of Earthquake Archaeological Effects (EAE) in archaeoseismology: Application to ancient remains of Roman and Mesoamerican cultures. Quaternary International, 242(1), 20-30.

- Rodríguez-Pascua, M. A., Benavente Escobar, C. L., Guevara, R., Grützner, C., Audin, L., Walker, R., García, B. & Aguirre, E. (2019). Did earthquakes strike Machu Picchu? Journal of Seismology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09877-4.

- Wimpenny, S., Copley, A., Benavente, C., & Aguirre, E. (2018). Extension and dynamics of the Andes inferred from the 2016 Parina (Huarichancara) earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 123(9), 8198-8228

Links

- ScienceMag article in English: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/10/machu-picchu-was-hit-strong-earthquakes-during-construction

- National Geographic article in Spanish: https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/dos-terremotos-sacudieron-machu-picchu-mientras-se-construia_14842

- Peruvian Times article in English: https://www.peruviantimes.com/13/earthquake-struck-machu-picchu-in-1450-study-concludes/31027/

- Portal Andina about the CUSCO-PATA Project (in Spanish): http://portal.andina.com.pe/edpespeciales/2018/machupicchu/index.html

No Comments

No comments yet.