During January 13-17, in 2020, Hokudan 2020, an international symposium on active faulting, was held in Awaji City, Japan, in order to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Kobe earthquake. Along with recent progress in active fault research, we discussed earthquake outreach just in front of the surface rupture of the earthquake. Here I want to share some stories behind the fault preservation museum in the earthquake memorial park and some ideas about what we can do to improve earthquake awareness.

Program and abstract volume are available from the meeting website:

https://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/kojiok/hokudan2020.html

The Kobe earthquake and the fault preservation museum

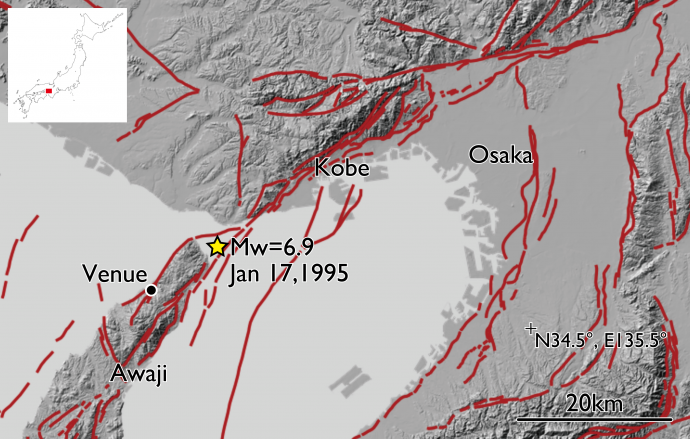

On January 17, 1995, the Mw 6.9 earthquake brought massive damage around Kobe and took 6,434 lives, leaving a strong imprint on Japanese society (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2020/01/16/editorials/learned-enough-1995-kobe-quake/#.XnB3uy2B3Yo).

Three years after the tragedy, the Nojima Fault Preservation Museum was built on Awaji Island, where most of the surface rupture appeared. There, you can see a clear surface offset, a paleoseismic trench wall, and a house that survived the earthquake even though it is right beside the fault. Everything in the museum is so beautifully preserved that you may feel like you witnessed the disaster.

preserved in the Nojima Fault Preservation Museum in Awaji City.

Just like we realize once again the importance of handwashing amid the coronavirus outbreak, it is not easy for people to improve their hazard awareness until it happens. In that sense, the museum has offered the legacy of the massive earthquake to over 9 million visitors and contributed a lot to earthquake education.

Issues behind the success: What to expect in preserving legacies of an earthquake

How was this museum established just three years after the quake? Talks at Hokudan 2020 and a conversation with museum staff taught me some key points to build such a museum.

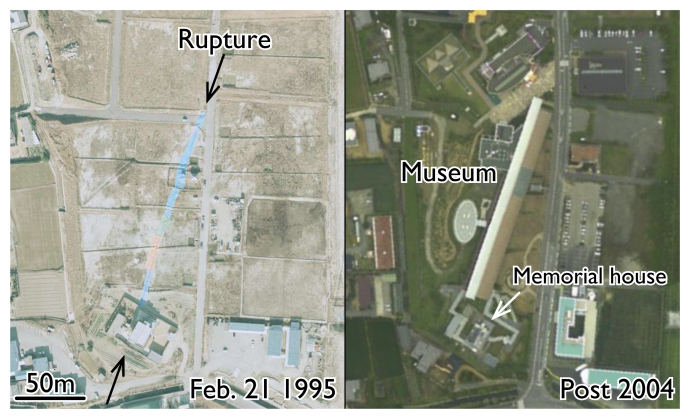

First of all, speed matters. Japanese researchers visited the surface rupture the day after the earthquake and soon asked the mayor of Hokudan Town (now Awaji City) to preserve the rupture. With enthusiastic support from the town, the surface rupture was covered with vinyl tarps four days after the earthquake. Another four days after that, researchers officially proposed conserving the rupture, and Hokudan Town started a project to establish the museum. Since the top priority in a post-disaster situation is to secure people’s lives, it would have been quite reasonable if the proposal had been dismissed when it was submitted to the town office. So, without the passion of the researchers and Hokudan Town, we might never have seen the great museum.

The surface rupture of the Kobe earthquake (January 17, 1995) is covered with blue tarps.

Memorial house survived the quake even though it is right next to the rupture.

On the other hand, quick action doesn’t always go smoothly in the aftermath of a destructive earthquake. Imagine that you were in a disaster and had no idea how to survive. You would probably want to forget the tragedy and return to ordinary life as soon as possible. When the researchers and the town announced the fault-preservation project, some residents opposed the plan, and the opposition continued even after the museum opened. This was because keeping the scars from the earthquake fresh reminded them of the catastrophe, which they were struggling to forget. So, it is true that quick action is indispensable to preserving a surface rupture, but we must never ignore the local people.

Engaging local authorities in a project is crucial to keep a fault preservation museum as a good reminder of a disaster. Now Awaji City holds public outreach events every year, and one of them took place after the Hokudan 2020. People of various backgrounds, such as geologists and national and local government officials, shared their experiences and discussed how we could use surface rupture of recent earthquakes for future education. The Educational Board of Hokudan Town has kept the rupture clean with the help of geologists. Besides, Hokudan Co., a local company, maintains the museum and organizes a group of people who share their experiences and memories of the disaster. Such cooperation helps the museum to catch public attention and to improve hazard awareness.

Get prepared for a future disaster as an earthquake geologist

No matter how much money a local/national government invests in hazard mitigation, it can be of no use unless citizens learn to get prepared for a future disaster. Despite the constant effort of people involved, the number of visitors to the museum has been declining from 2,820,000 in 1998 to 136,000 in 2017. I have no doubt that establishing a fault preservation museum is an excellent way to communicate seismic hazard to the public, and it is equally important to think about how we can keep the museum attractive for a long time. If you have any thoughts or wish to build another fault museum, you should come to Hokudan 2025 and discuss how we can prepare for a future seismic hazard!

Last but not least, it is truly great for the Hokudan symposium to have been held every five years since 2000. I cannot thank enough Operational Committee of the Hokudan International Symposium on Active Faulting (Chairman: Takashi Nakata, Emeritus Professor at Hiroshima University) and many organizations for hosting the Hokudan 2020.

No Comments

No comments yet.