By Jacek and Christoph

Paleoseismology was developed in places where faults behave well. In California, Anatolia, or along major plate-boundary faults, earthquakes repeatedly break the surface in rather short recurrence intervals, and they form long scarps. In such settings, tectonic geomorphology, subsurface data, and empirical scaling laws between rupture lengths and offset tend to point in the same direction. These regions have been essential for developing paleoseismic methods—but they have also shaped our expectations in ways that are not always transferable to other settings.

Mature orogens and slowly deforming mountain belts are different. Fault slip rates are low and earthquake recurrence intervals are long, often tens of thousands of years. Erosion, solifluction, soil creep, and other types of mass movements modify the landscape faster than tectonics can do. This is especially true in areas that are glaciated during the ice ages. As a result, the geological record of faulting is incomplete by default. Scarps are degraded, stratigraphic markers are rare, and the link between surface morphology and fault kinematics is often ambiguous. None of this means that these regions are tectonically inactive. It means that their activity is harder to read.

An example from Poland

The short fault scarp in the Podhale Basin of the Central Western Carpathians (Poland) illustrates this problem. The scarp is only about 3 km long, yet it reaches several metres in height and cuts across several ridges in a straight line. It lies in a region usually considered to be of low to moderate seismicity. At first glance, the scarp looks like a minor geomorphic feature. A closer inspection reveals it to be something far more awkward.

Two inconsistencies make it interesting. The first is the ratio between scarp length and height. According to commonly used displacement–length scaling relationships like Wells & Coppersmith, a surface rupture this short should not produce a scarp several metres high – and multiple surface ruptures shouldn’t be preserved given the region’s overall setting. The second inconsistency appears in the paleoseismic trench. While the surface morphology suggests cumulative offsets of several metres (although it’s not clear how they could be preserved), the vertical displacement exposed in the trench is less than half a metre. Together, these observations are difficult to reconcile with standard paleoseismic expectations.

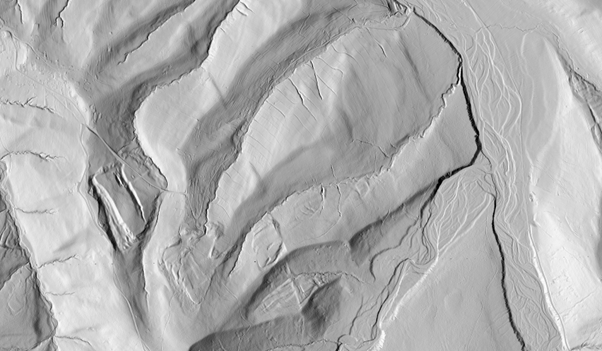

At the surface, the Brzegi scarp looks simple. LiDAR data show a straight, continuous lineament that can be traced across multiple ridges. Its clearly asymmetric: on north-facing slopes and ridge crests, the scarp is well developed, whereas on south-facing slopes it becomes muted or disappears. This pattern is systematic, not random, and points to the geometric relationship between the fault’s slip vector and slope azimuth. Pure dip-slip doesn’t work. A dextral-oblique fault with a significant strike-slip component fits the observations best.

Not a landslide scar

Equally important is what the scarp does not look like. Nearby landslides show rectangular head scarps, probably controlled by the structural of the bedrock. They exhibit internal deformation and clear downslope transport zones. Importantly, they are tied to individual slopes of course. The Brzegi scarp, by contrast, is linear, crosses drainage divides, and extends well beyond the scale of any single hillslope. Therefore, it surely is not (solely) of gravitational origin.

Geophysical data support this view. Electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and induced polarization (IP) profiles consistently image a narrow, steeply anomaly zone beneath the scarp. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) shows disrupted reflectors and zones of intense scattering, interpreted as fractured and water-rich material. These anomalies persist even where the surface scarp is almost imperceptible, suggesting that the fault itself is continuous and not simply a superficial geomorphic feature caused by a non-tectonic process.

The paleoseismic trench provides the most direct evidence, and the greatest frustration. Instead of a clean slip surface, deformation appears as a narrow zone of highly fragmented bedrock and clay-rich material that cuts through both bedrock and the overlying slope deposits. The layers is slightly folded locally, blocks are rotated, and grain size decreases sharply within this zone. Clear kinematic indicators, such as slickensides, are absent. Stratigraphic relationships point to a vertical separation of roughly 40 cm. This is difficult to square with the several metres of relief expressed at the surface.

The trench also exposes thick packages of weathered clay and colluvium, largely inherited from periglacial processes and long-term slope reworking. These deposits thicken toward the scarp and show signs of post-deformational reorganization consistent with slow creep and solifluction. Their geometry suggests that fault movement weakened the slope locally, creating conditions under which gravitational processes could progressively enhance the surface relief of the scarp. In this way, a modest tectonic offset could be amplified over time without leaving an equivalent signature in the stratigraphic record.

How old is it?

Because no datable material was available in the trench, we turned to scarp diffusion modeling to constrain the timing of scarp formation. This approach treats scarp degradation as a diffusion process, in which sediment flux is proportional to slope gradient. The model is simple, but its assumptions are rarely fully met, particularly in clay-rich landscapes affected by climatic fluctuations. The method also assumes no bedrock and single event ruptures…

In this case, the diffusion coefficient was calibrated using a better-dated post–Last Glacial Maximum scarp along the Sub-Tatra Fault (Pánek et al. 2020; Geomorphology doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107248), assuming broadly comparable geomorphic conditions. The resulting coefficient falls within the range reported from other temperate, postglacial settings. Still, the modeled ages span a wide interval, from about 10 to 50 ka. Rather than providing a precise age, the modeling places the formation of the scarp in the late Pleistocene. That large uncertainty is expected, and perhaps it’s even a bit larger given that our case violates some of the assumptions. But since there’s no other way to date it, we wanted to at least get a general idea of how old it might be.

What’s the solution?

Several explanations could account for the observed inconsistencies. Distributed creep within clay-rich material may exaggerate surface relief. However, we don’t see any hints for that in the morphology. An oblique slip dominated by strike-slip offset could produce large apparent offsets on certain slope aspects while leaving only small vertical separation in the trench. Fault segmentation or linkage at depth might allow greater cumulative displacement than the mapped surface trace suggests. Each of these ideas is reasonable. None can be demonstrated conclusively with the available data, and none resolves all aspects of the problem.

This ambiguity was a major point of discussion during peer review. It raises a broader question: what should we expect paleoseismology to deliver in mature orogens or slowly deforming regions? In many studies, uncertainty is treated as something to be eliminated through more data and more refined methods. In the Podhale Basin, however, the limitations are not primarily methodological. They stem from the nature of the geological archive itself. In slowly deforming landscapes dominated by efficient surface processes, key pieces of information may simply not be preserved.

Uncertainties won’t go away

Rather than forcing a single interpretation, we chose to make this limitation explicit. The Brzegi Fault study is therefore somewhat uncomfortable and deliberately so. It presents the data, tests competing ideas, and accepts where interpretation breaks down. This does not yield a clean earthquake chronology or a well-constrained magnitude estimate. What it does offer is a realistic picture of how active tectonics may appear in a mature orogen.

The broader context matters. The Carpathians form a more than 1200-km-long mountain chain that has been studied intensively for over a century, yet this work represents the first paleoseismic trench excavated along its length. That fact alone is telling. Paleoseismology is most effective where deformation is fast and the environment is suitable. The Brzegi scarp suggests otherwise. Active tectonics in such regions may be subtle and at odds with expectations derived from plate-boundary settings.

Paleoseismology must engage with these awkward cases. Not every fault will yield a clear rupture history or a neat solution. Some will instead expose the limits of our tools and assumptions. The short scarp in the Podhale Basin does exactly that, and in doing so, it reminds us that uncertainty, when carefully documented, is not a weakness, but an essential part of understanding tectonics in slowly deforming regions.

Reference

-

Szczygieł, J., Zasadni, J., Kłapyta, P., Woszczycka, M., Gaidzik, K., Mendecki, M., Sobczyk, A. & Grützner, C. (2025). The curious case of a short fault scarp in the Podhale Basin: Implications for late Pleistocene geodynamics of the central Western Carpathians. Geomorphology, 110134.

No Comments

No comments yet.